International Year of the Woman Farmer 2026

I love farmers. 2026 is the International Year of the Woman Farmer. Farms all over…

On May 16-26, the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) will host the Bonn Climate Change Conference. In the wake of the December signing of the Paris Agreement, the event will focus on implementation of this landmark pact through the First session of the Ad Hoc Working Group on the Paris Agreement. At the same time, this venue will also advance long-running processes such as the Subsidiary Body for Scientific and Technological Advice (SBSTA), which will hold its forty-fourth session. So the Bonn conference represents both new and long-term international collaboration to tackle global climate change.

In their reflections note for this event, the outgoing and incoming Conference of the Parties presidents state that “No issue has been left behind.” Indeed, agriculture, which has struggled at times for visibility in the UNFCCC negotiations, will be featured through two SBSTA sessions at the Bonn conference focused on adaptation measures and enhancement of productivity. These sessions will offer a venue for governments and others to explore this sector’s role in the climate response, including the agriculture-related strategies put forth in 80% of the submitted Intended Nationally Determined Contributions.

Mobilizing the agriculture sector in the fight against climate change means finding the best ways to simultaneously reduce net greenhouse gas emissions, increase resilience to extreme weather and other changes, and strengthen food security. This may sound a bit like juggling while riding a bicycle on a tight rope, but luckily the opportunities in agriculture are many.

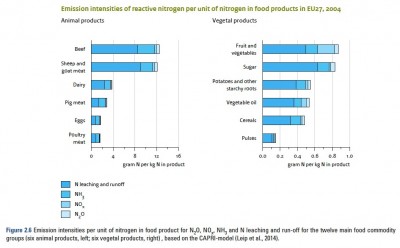

As just one example, a recent report, “Nitrogen on the table: The influence of food choices on nitrogen emissions, greenhouse gas emissions and land use in Europe” illustrates how increasing production and consumption of pulse crops – like beans, peas, lentils, and chickpeas – can increase a high-protein food source while reducing emission of nitrous oxide and other greenhouse gases.

Unlike other crops which get essential nitrogen from soil and fertilizers, pulses fix their nitrogen from the air – with essential help from soil bacteria – which means farmers don’t need to add nitrogen fertilizers. In fact, pulse crops can add nitrogen to soil that nourishes other crops in the rotation. Since producing nitrogen fertilizers uses a lot of energy, growing pulse crops cuts down on greenhouse gas emissions at fertilizer plants and nitrous oxide emissions from the soil surface.

Farming systems around the world are incredibly diverse so there will be many different pathways to achieving mitigation, adaptation, and food security goals. The tremendous diversity among pulse crops means that this nutritious food can be grown in most agricultural regions and be part of national efforts to deliver on climate change commitments.